Lotta Crabtree. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. I love the contrasts in this photo, the sweet innocence of her expression, ribbons on her hat, childish curls in her hair, her head turned shyly from the camera...and she's smoking a cigar!

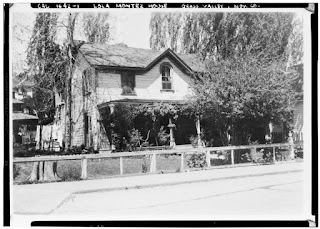

In spite of her tough-little-girl look in the above photo, "generosity and compassion" were the words most often used to describe Lotta Crabtree. Along with her mentor, Lola Montez, Crabtree was one of the most famous entertainers in the American Old West. She was beautiful, charming and charasmatic, but in all fairness, she did owe her success to Montez, who taught Crabtree how to use her charm and develop a bold, beguiling personality. It was serendipity, magic, a toss of the dice that brought these two together. Lola's career was waning when they met, and Crabtree was a child, but this was her fate, to learn from Lola Montez, one of the most famous dancers in America, and perhaps the world. The fact that they were both in small town Green Valley, California at the same time was pure chance, but when Montez met Crabtree it was magic, and what came next is a story that begs to be told.

Lotta Crabtree. Theatrical and Circus Life: 1893. The Library of Congress: Public Domain.

The importance of the story of Lola Montez and Lotta Crabtree lies in more than their friendship or their talent. These were two women who struggled to build careers during distinctly different periods in the history of the American Old West--the early, wild years belonged to Lola Montez and the later, more refined years of Old West entertainment were ruled by Lotta Crabtree. But they did have much in common, primarily the fact that both women loved to dance and entertain and displayed great talent at a young age.

They also had similar personalities. Lola Montez, "The Spanish Dancer," is described in news articles and other historical documents as spoiled, half-wild, adventurous, notorious, stubborn, and of course, a woman of great beauty. But this was only part of the story of Lola Montez. Her life was a struggle from the day she was born, and this formed her personality. What the journalists often failed to report was that Montez cared deeply about the status of women in the 1800s and used most of her earnings to help other women who were also struggling to survive in the American Old West.

Miss Lotta

Lotta Crabtree's background was far different from that of Lola Montez. She did not come from a wealthy, noble family, but was raised with loving parents who followed the trail to the West. She also had great compassion for others, and perhaps this was part of the life lesson Montez passed on to her protege, to help others in any way she could.

Photo of Lotta Crabtree taken by Mathew Brady. Date unknown, public domain.

Lotta had many nicknames. By age 12, she was referred to as “Miss Lotta, the San Francisco Favorite.” She was also known as "The Nation's Darling." The press described her as "winsome, saucy, and possessing infectious gaiety, charm," and of course, a great beauty. And by the time she retired, she was referred to as "The Richest Entertainer in America."

Her public reputation is far less scandalous than that of Montez, but as I said before, life was easier for Crabtree, times were different, and Montez started her life and career on the opposite side of the world. The American Old West was "wild," but perhaps not as judgmental toward women as the places Montez lived when she was young.

Unlike Montez, who was forced to marry many times to survive, Crabtree never felt that need and remained single her entire life. The life situation of Lola Montez was shared by women for hundreds of years, women who had to choose marriage, a service career, or prostitution.

Gold

Lotta Crabtree's family traveled West in search of gold. They encouraged Lotta's endeavors, but didn't seem to try to force her into anything. In the Old West, during the Gold Rush years when miners were plenty and women were few, (and miners had money!) women found another way to supplement their income and maintain a certain amount of freedom by singing and dancing. Therefore, Crabtree's desire to dance and her great skill is equally legendary as that of Montez, because Lotta Crabtree lived to dance.

Montez Meets Crabtree

Lotta was born in 1847 in New York. Her parents named her Charlotte Mignon Crabtree, and over the years, Charlotte became Lotte, which became Lotta. When Lotta was a toddler her father moved the family to California to join the Gold Rush, possibly part of the "49ers. (I assumed they were associated with the mass gold rush of 1849 because of the timeline of their move, and because the entire family moved to California. However, many men left their families behind because gold rush camps could be dangerous, expensive, and deadly, and Lotta's entire family moved, so I could be mistaken). Lotta was approximately six years old when her family arrived in San Francisco, which would have been 1853.

The Crabtree family settled in the Grass Valley Mining Camp near the home of Lola Montez, the Countess of Landsfeldt. According to legend, Lotta was playfully dancing in the street while waiting for her parents when she attracted the attention of Montez. Montez was enchanted. She gave Lotta a few short, simple instructions, and realized the girl had talent. Montez convinced Lotta's parents that the child could help support her family as a dancer, and considering the past struggles of Lola Montez, I do believe support for the girl's family would have been her primary concern.

Montez offered to teach the Lotta "The Spanish Dance." Lotta Crabtree's parents, still struggling financially from their move, eagerly agreed with a bit of pressure from their charismatic daughter.

The Famous Meeting at the Fountain

There are more than a few legends circulating about this meeting. Lotta wasn't just dancing in the street, she was also dancing near a popular, but aging fountain near Market and Kearny Streets and attracting a crowd. Lotta paused when she noticed a tired, hot horse standing nearby. She brought water to the horse from the fountain. This random act of kindness did not go unnoticed by the people of San Francisco. Lotta had established a sweet, innocent child reputation before she even reached the stage.

In 1875, after she had saved a small fortune, Lotta Crabtree returned to the fountain. She paid to have it restored and dedicated "Lotta's Fountain" to the people of San Francisco.

Lotta first performed in 1855 in front of a group of miners. She was born in 1847 which means she was eight years old when she first performed. Over the next four years she toured throughout California visiting many mining camps and appearing in theaters in San Francisco. She danced, sang, and performed short acting roles that were written just for her.

Her first official performance was in Petaluma, California in "Loan of a Lover." In 1864 she performed in New York City, but reviews were poor. After touring the country for three years she again performed in New York City in "Little Nell and the Marchioness," adapted from "The Old Curiosity Shop" by Charles Dickens, who was popular at this time.

By the 1870s, Lotta had her own touring company. The reviews of her touring company were favorable. As for her performance, she was often compared to a sprite, or fairy, which I find interesting since in one of her most popular photos, Lotta she appears to be a child smoking a cigarette (photo at top of page).

Lotta's Life

Lotta's family traveled with her as she toured the Old West. Her mother was her manager and she did not allow Lotta to neglect her education. Lotta was proficient in the French language and in painting.

At the peak of her career, Lotta Crabtree was earning $5000 a week, and in contemporary dollars that would be approximately $125,000 a week according to the Inflation Calculator. Crabtree invested in houses and land, bonds, and racehorses. She also donated large sums to charities. Lotta's private home was the 18-room summer cottage in Mount Arlington, New Jersey, on the shores of Lake Hopatcong.

Lotta Crabtree's Retirement

Lotta retired in 1891 at the age of 44, which may seem young now, but in the 1800s the average life span for women was in the 40s. At the time of her retirement she was the richest female performer in the United States.

Lotta's last performance was for "Lotta Crabtree Day" at the San Francisco at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 in San Francisco. Then she retired to her estate on Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey.

Lotta Crabtree never married. She died in 1924 at the young age of 77 in her New York home. She was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York.

When she died, Lotta Crabtree left over $4 million dollars to charities for veterans, animals, and aging actors.

Sources:

Her public reputation is far less scandalous than that of Montez, but as I said before, life was easier for Crabtree, times were different, and Montez started her life and career on the opposite side of the world. The American Old West was "wild," but perhaps not as judgmental toward women as the places Montez lived when she was young.

Unlike Montez, who was forced to marry many times to survive, Crabtree never felt that need and remained single her entire life. The life situation of Lola Montez was shared by women for hundreds of years, women who had to choose marriage, a service career, or prostitution.

Gold

Lotta Crabtree's family traveled West in search of gold. They encouraged Lotta's endeavors, but didn't seem to try to force her into anything. In the Old West, during the Gold Rush years when miners were plenty and women were few, (and miners had money!) women found another way to supplement their income and maintain a certain amount of freedom by singing and dancing. Therefore, Crabtree's desire to dance and her great skill is equally legendary as that of Montez, because Lotta Crabtree lived to dance.

Lotta Crabtree, full-length portrait in costume for a theatrical role, dressed as a child, and yet, she appears to be once again smoking a cigar! Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

Montez Meets Crabtree

Lotta was born in 1847 in New York. Her parents named her Charlotte Mignon Crabtree, and over the years, Charlotte became Lotte, which became Lotta. When Lotta was a toddler her father moved the family to California to join the Gold Rush, possibly part of the "49ers. (I assumed they were associated with the mass gold rush of 1849 because of the timeline of their move, and because the entire family moved to California. However, many men left their families behind because gold rush camps could be dangerous, expensive, and deadly, and Lotta's entire family moved, so I could be mistaken). Lotta was approximately six years old when her family arrived in San Francisco, which would have been 1853.

The Crabtree family settled in the Grass Valley Mining Camp near the home of Lola Montez, the Countess of Landsfeldt. According to legend, Lotta was playfully dancing in the street while waiting for her parents when she attracted the attention of Montez. Montez was enchanted. She gave Lotta a few short, simple instructions, and realized the girl had talent. Montez convinced Lotta's parents that the child could help support her family as a dancer, and considering the past struggles of Lola Montez, I do believe support for the girl's family would have been her primary concern.

Montez offered to teach the Lotta "The Spanish Dance." Lotta Crabtree's parents, still struggling financially from their move, eagerly agreed with a bit of pressure from their charismatic daughter.

Lotta's Fountain in 1905, looking northeast along Market Street; the Palace Hotel is at right and the Ferry Building's clock tower is in the distance. Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

There are more than a few legends circulating about this meeting. Lotta wasn't just dancing in the street, she was also dancing near a popular, but aging fountain near Market and Kearny Streets and attracting a crowd. Lotta paused when she noticed a tired, hot horse standing nearby. She brought water to the horse from the fountain. This random act of kindness did not go unnoticed by the people of San Francisco. Lotta had established a sweet, innocent child reputation before she even reached the stage.

In 1875, after she had saved a small fortune, Lotta Crabtree returned to the fountain. She paid to have it restored and dedicated "Lotta's Fountain" to the people of San Francisco.

Flamenco Dance, oil on canvas, by Ricard Canals i Llambí (1876–1935). Public Domain.

The Spanish Dance

When historians discuss Lotta Crabtree they refer to her dance style as the same "Spanish Dancing" performed by Lola Montez. After searching through numerous sources in an attempt to identify the exact dance that Lola Montez performed and taught to Lotta Crabtree, I am still unable to accurately identify if she performed a variety of dances or Flamenco.

However, I did discover that when people refer to Spanish Dance, they are often referring specifically to Flamenco, which is a dance based on the folklore traditions of Andalusia Spain. Its origin is traced back to the gypsies of Romani, Castilians, Moors and Andalusians , as well as Sephardi Jews in Andalusia. The gowns worn by dancers had extensive embellishments. The combination of exotic dance moves, colorful gowns, and hypnotic music was enchanting to audiences in the Old West.

A Popular Young Dancer

Her first official performance was in Petaluma, California in "Loan of a Lover." In 1864 she performed in New York City, but reviews were poor. After touring the country for three years she again performed in New York City in "Little Nell and the Marchioness," adapted from "The Old Curiosity Shop" by Charles Dickens, who was popular at this time.

By the 1870s, Lotta had her own touring company. The reviews of her touring company were favorable. As for her performance, she was often compared to a sprite, or fairy, which I find interesting since in one of her most popular photos, Lotta she appears to be a child smoking a cigarette (photo at top of page).

Lotta's Life

Lotta's family traveled with her as she toured the Old West. Her mother was her manager and she did not allow Lotta to neglect her education. Lotta was proficient in the French language and in painting.

At the peak of her career, Lotta Crabtree was earning $5000 a week, and in contemporary dollars that would be approximately $125,000 a week according to the Inflation Calculator. Crabtree invested in houses and land, bonds, and racehorses. She also donated large sums to charities. Lotta's private home was the 18-room summer cottage in Mount Arlington, New Jersey, on the shores of Lake Hopatcong.

Lotta Crabtree's Retirement

Lotta retired in 1891 at the age of 44, which may seem young now, but in the 1800s the average life span for women was in the 40s. At the time of her retirement she was the richest female performer in the United States.

Lotta's last performance was for "Lotta Crabtree Day" at the San Francisco at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 in San Francisco. Then she retired to her estate on Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey.

Lotta Crabtree never married. She died in 1924 at the young age of 77 in her New York home. She was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York.

When she died, Lotta Crabtree left over $4 million dollars to charities for veterans, animals, and aging actors.

- Crabtree, Charlotte. The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- Crabtree, Charlotte. Encyclopedia Brittanica Online. Accessed May 14, 2017.

- "Flamenco." Wikipedia. Accessed July 25, 2019.

- "Flamenco Dance." Ricard Canals i Llambí, circa 1935. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed July 25, 2019.

- "Lotta Crabtree." Death Valley Days. Season 2, Episode 9, first aired January 5, 1954.